Child pipelines in GitLab allow you to create more streamlined and reusable behaviour. They are separate pipelines that are triggered from a parent pipeline.

Why use child pipelines?

When a normal pipeline runs, all the code of the files you included gets dumped into .gitlab-ci.yml. This is why you have to give each job a unique name and repeatedly include the same rules so some only execute on a merge request or in the main branch. It’s the equivalent of spaghetti code and makes your pipeline more complex and difficult to updates.

A child pipeline is a new context with its own subset of jobs. Any rules you have only need to be processed when deciding to launch the child pipeline. This leads to leaner and more reusable code. Modifications are also easier because you only have to focus on the behaviour of a small subset of jobs.

Here are a few cases where child pipelines make the most sense:

- Breaking up a monolith: Because

.gitlab-ci.ymland all templates and other included files get combined into one huge file when the pipeline runs, GitLab pipelines are monolithic. Child pipelines allows you to break up that monolith, giving you better isolation on variables and allowing you to usedefaultin ways that make your code easier to manage. In a previous blog, I showed a method for dealing with monorepos, but this also showed the limitations of having all your code accrete in one huge file. - Self-contained, reusable code: Each child pipeline can be its own self-contained set of behaviours, allowing you to make modifications to the code without fear of it breaking the entire pipeline.

- Reduced complexity: When you spawn multiple child pipelines and these run in parallel, having each branch’s behaviour in its own self-contained set of files makes thinking about the problem space easier than if everything were collapsed into one huge file.

- Isolation: By default, if a child pipeline fails, the parent job that triggered it does not. This can be useful if you’re running something like a lint check, which could fail, but shouldn’t prevent the build from completing.

A basic parent/child pipeline

The following is a stripped down example.

You can find the source code in the reference repository.

First, let’s define the child pipeline file child-pipeline.yml:

child-job:

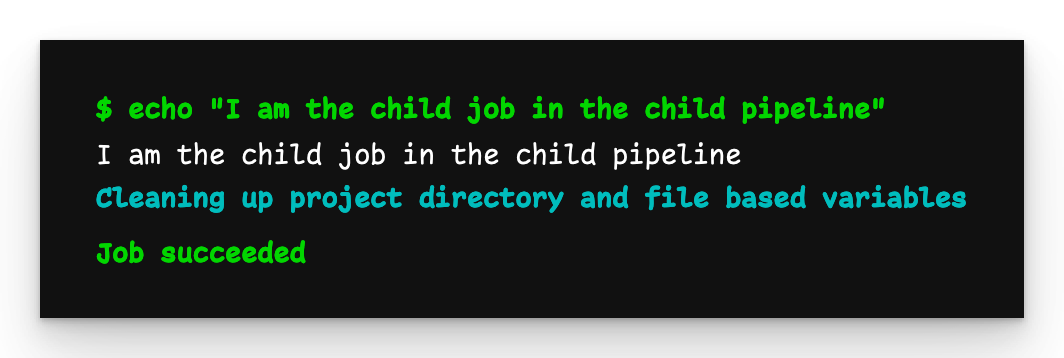

script: echo "I am the child job in the child pipeline"

This does nothing more than print a message. Next, we define the .gitlab-ci.yml file:

parent-trigger-job:

trigger:

include:

- local: child-pipeline.yml

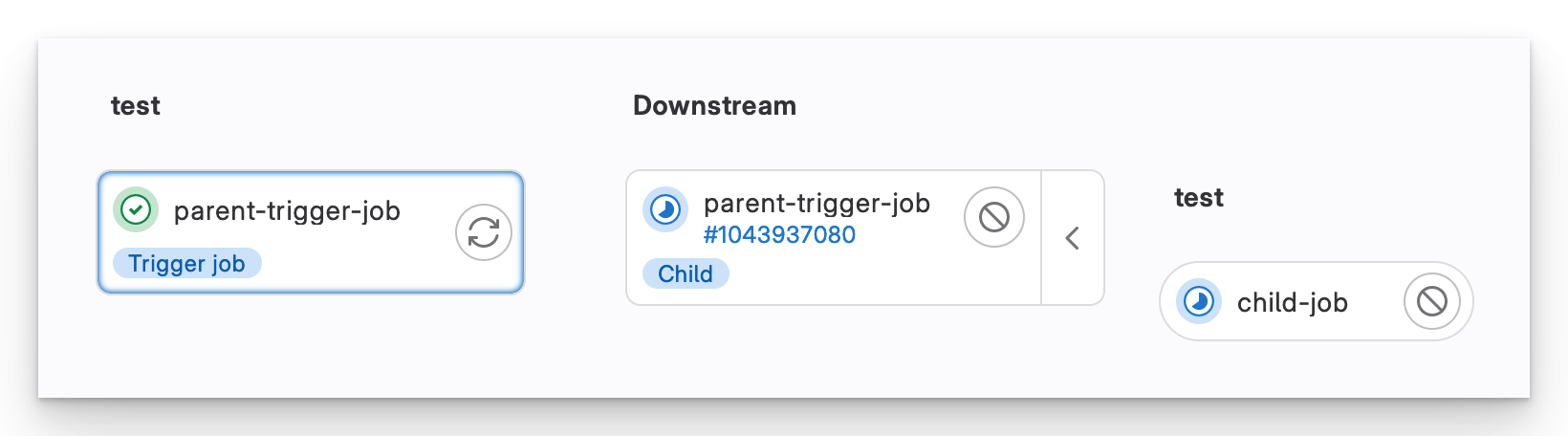

When we push the code, the pipeline starts like normal, then spawns the child pipeline.

Downstream pipeline

The interface for a parent/child pipeline looks different to a normal pipeline. We see that there is a downstream pipeline and the job(s) it executes.

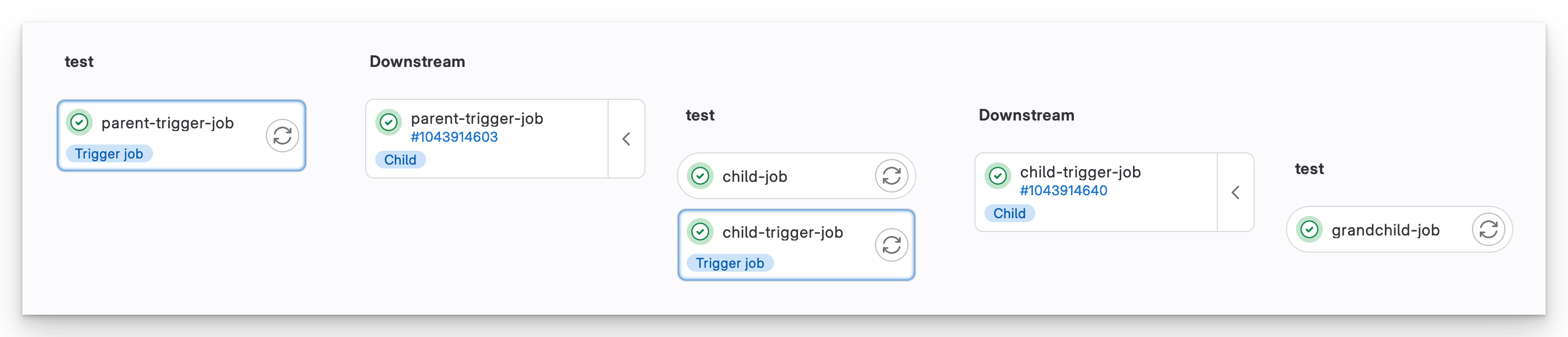

Nested child pipelines

It’s not only possible for a parent pipeline to spawn child pipelines, but those children can, in turn, spawn their own child pipelines. However this parent/child/grandchild depth is the limit of what GitLab will allow.

You can find the source code in the reference repository.

We’ll use the same .gitlab-ci.yml file as before:

parent-trigger-job:

trigger:

include:

- local: child-pipeline.yml

Now we add a new job to child-pipeline.yml:

child-job:

script: echo "I am the child job in the child pipeline"

# New job to trigger a child pipeline

child-trigger-job:

trigger:

include:

- local: grandchild-pipeline.yml

This new job, works the same as the parent-trigger-job. Lastly, we add grandchild-pipeline.yml:

grandchild-job:

script: echo "I am the grandchild job in the grandchild pipeline"

Nested downstream pipelines

With this nesting, GitLab allows you to fan out your behaviour in more interesting ways.

Passing variables to child pipelines

Even though child pipelines run independently of their parents, it is possible to share variables with them.

You can find the source code in the reference repository.

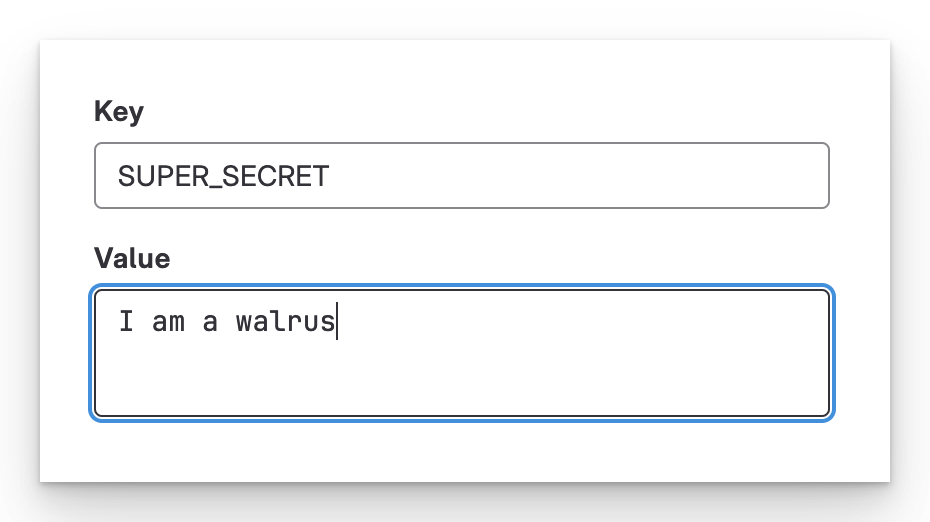

GUI variables

Let’s start with the easiest example: GUI-defined variables. I define a variable called SUPER_SECRET under Settings > CI/CD > Variables.

Define a variable in the GUI

Again, we’ll start with a .gitlab-ci.yml file:

parent-job:

script:

- echo "The GUI-defined SUPER_SECRET is $SUPER_SECRET"

parent-trigger-job:

trigger:

include:

- local: child-pipeline.yml

Next comes child-pipeline.yml:

child-job:

script:

- echo "The GUI-defined SUPER_SECRET is $SUPER_SECRET"

child-trigger-job:

trigger:

include:

- local: grandchild-pipeline.yml

Lastly, we define grandchild-pipele.yml:

grandchild-job:

script:

- echo "The GUI-defined SUPER_SECRET is $SUPER_SECRET"

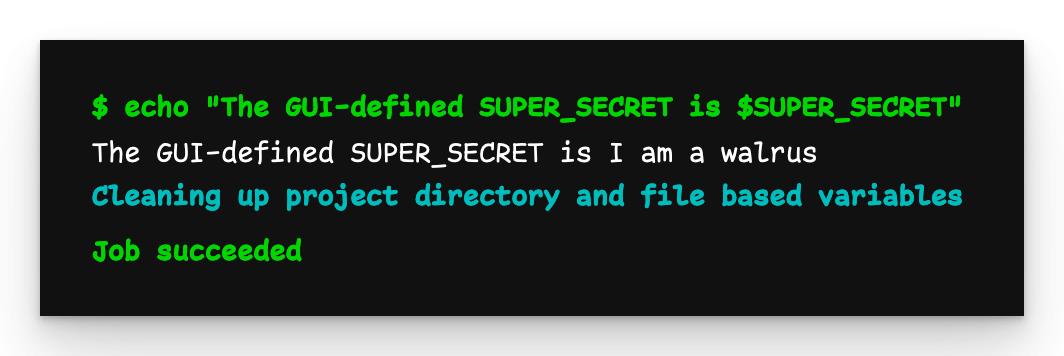

Parent, child, grandchild output

The output from all three pipelines is the same: I am a walrus. This is because while they run independently of each other, they all run in the context of the repository.

YAML-define variables

The situation is not quite the same with YAML-defined variables.

Let’s add two variables to .gitlab-ci.yml:

VERSION: YAML-globalAPI_KEY: Job-local

variables:

VERSION: 0.1.0 # Global variable

parent-job:

script:

- echo "The GUI-defined SUPER_SECRET is $SUPER_SECRET"

parent-trigger-job:

variables:

API_KEY: api-key-value # Job-local variable

trigger:

include:

- local: child-pipeline.yml

We update child-pipeline.yml to echo these new variables and define its own global variable:

ENVIRONMENT: YAML-global (child)

variables:

ENVIRONMENT: test # Child-level global variable

child-job:

script:

- echo "The GUI-defined SUPER_SECRET is $SUPER_SECRET"

- echo "Using API KEY $API_KEY for version $VERSION"

child-trigger-job:

trigger:

include:

- local: grandchild-pipeline.yml

Now we update grandchild-pipeline.yml to echo all variables:

grandchild-job:

script:

- echo "The GUI-defined SUPER_SECRET is $SUPER_SECRET"

- echo "I am using API KEY $API_KEY for version $VERSION in the $ENVIRONMENT environment"

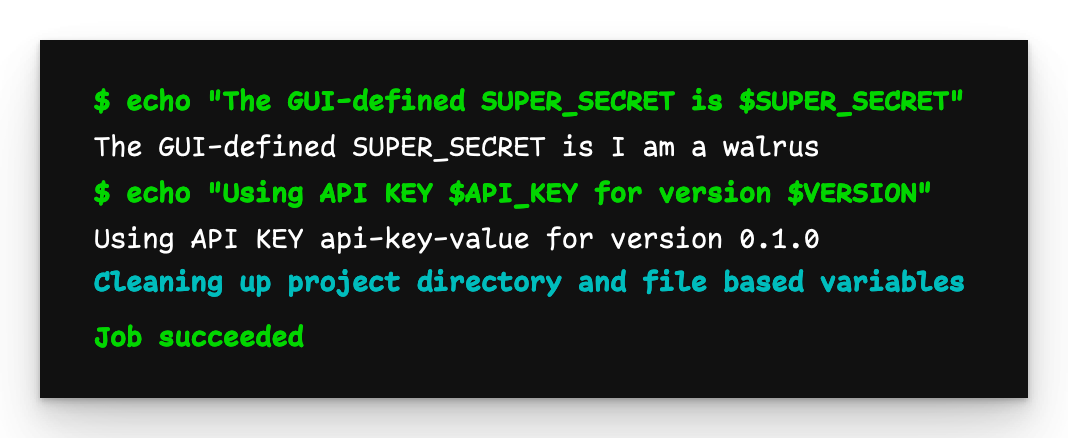

The output from parent-job remains the same, so let’s see what child-job prints:

Child pipeline output

The output is as we expect: The API_KEY and VERSION variables are successfully passed to the child pipeline.

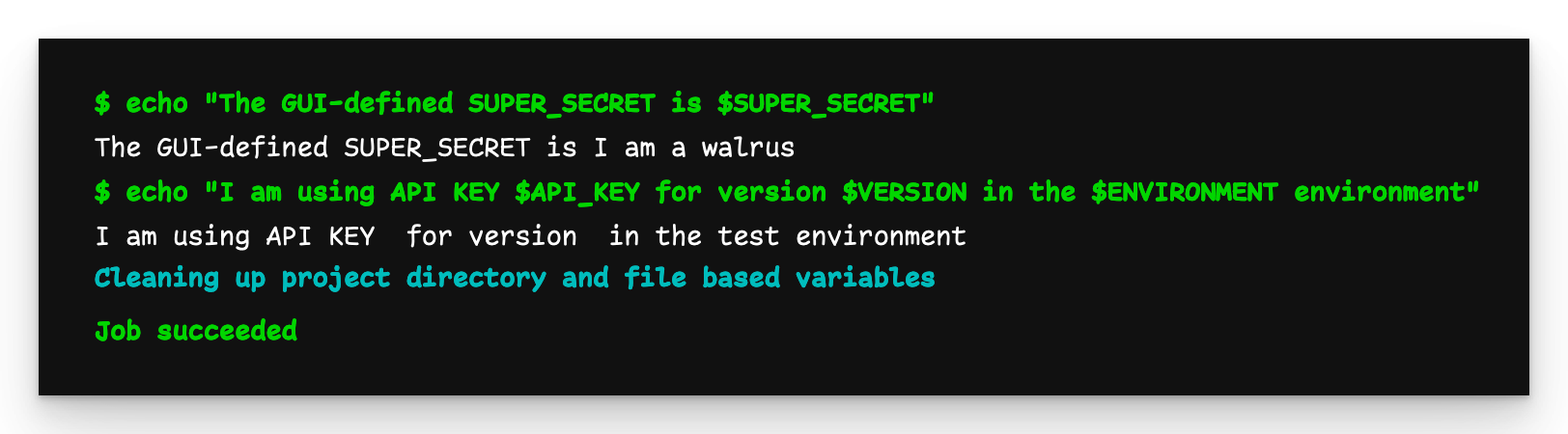

Grandchild pipeline output

However, the output of the grandchild pipeline is not the same. We see that the global variable ENVIRONMENT defined in the child pipeline passes to the grandchild, but API_KEY and VERSION, as defined in the parent, are not. From this it is clear that YAML-defined variables are only visible to their immediate children.

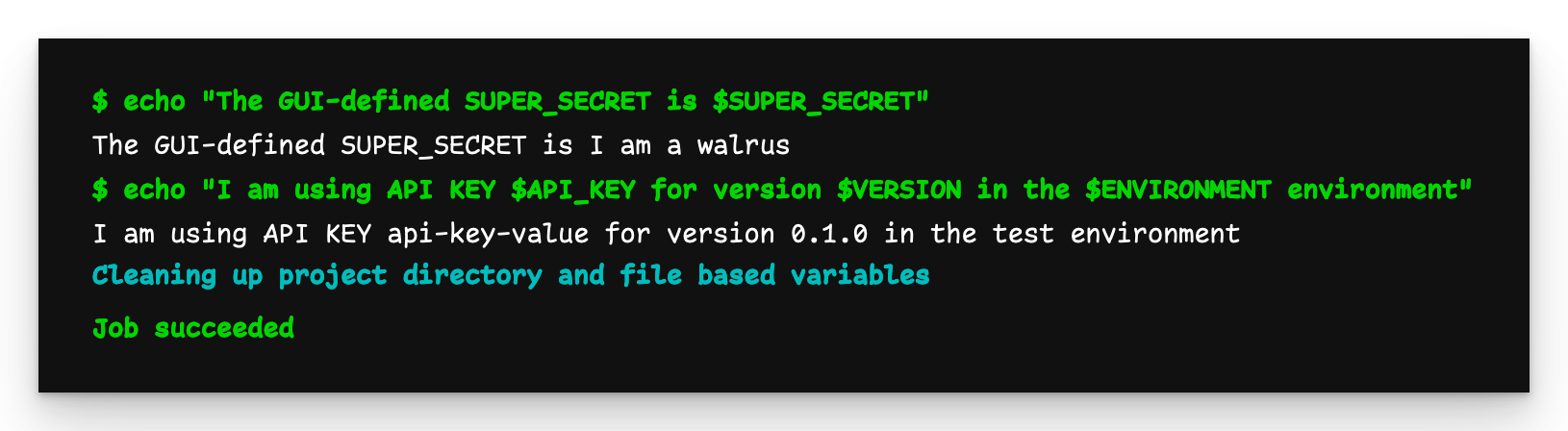

How do we make API_KEY and VERSION available to the grandchild pipeline? We have to propagate them manually. We update child-pipeline.yml and redefine those variables:

variables:

ENVIRONMENT: test

API_KEY: $API_KEY # Redefine the API_KEY variable

VERSION: $VERSION # Redefine the VERSION variable

child-job:

script:

- echo "The GUI-defined SUPER_SECRET is $SUPER_SECRET"

- echo "Using API KEY $API_KEY for version $VERSION"

child-trigger-job:

trigger:

include:

- local: grandchild-pipeline.yml

Grandchild pipeline output (final)

Now, the output from grandchild-job is as we expect.

Preventing global variables being passed to a child

What if we don’t want to pass variables to a child pipeline?

You can find the source code in the reference repository.

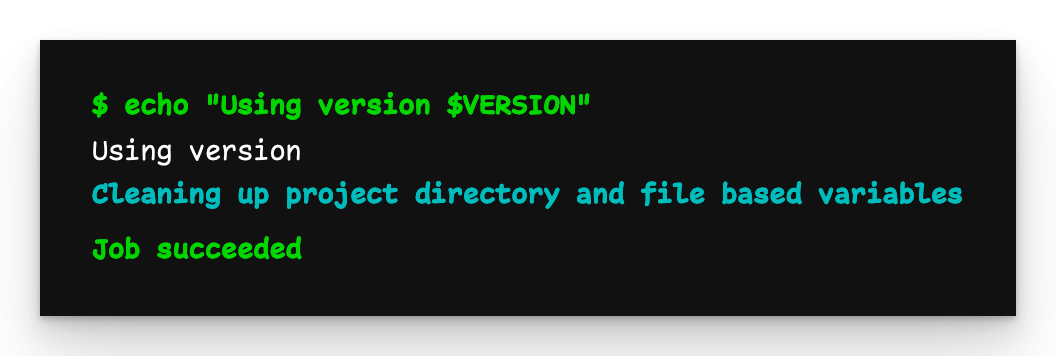

We can use inherit:variables:false in gitlab-ci.yml to prevent global variables from passing to the child pipeline:

variables:

VERSION: 0.1.0

parent-trigger-job:

inherit: # Prevent global variables

variables: false # being passed down

trigger:

include:

- local: child-pipeline.yml

While this prevents YAML-global variables passing down, you’re still free to include a

variablessection in your triggering job and those will get passed to the child.

Next, we define child-pipeline.yml:

child-job:

script:

- echo "Using version $VERSION"

Child pipeline output

As we can see, the VERSION global variable did not pass to the child pipeline.

Passing files to child pipelines

It’s not only possible to pass variables to child pipelines, but files, too.

You can find the source code in the reference repository.

Here is a .gitlab-ci.yml file that creates and stores a file:

create-file-job:

stage: build

script:

- echo "Important stuff" > file.txt # Create the file

artifacts: # Upload

paths: # the file

- file.txt # as an artifact

parent-trigger-job:

stage: test

trigger:

include:

- local: child-pipeline.yml

variables:

PARENT_PIPELINE_ID: $CI_PIPELINE_ID # This variable is important

Next, let’s create a child-pipeline.yml file that downloads the file:

child-job:

needs:

- pipeline: $PARENT_PIPELINE_ID # Reference to the parent pipeline

job: create-file-job # The job that creates the file

script: cat file.txt

You must pass the parent’s pipeline id (

$CI_PIPELINE_ID) to the child so it can identify the job that creates the file.

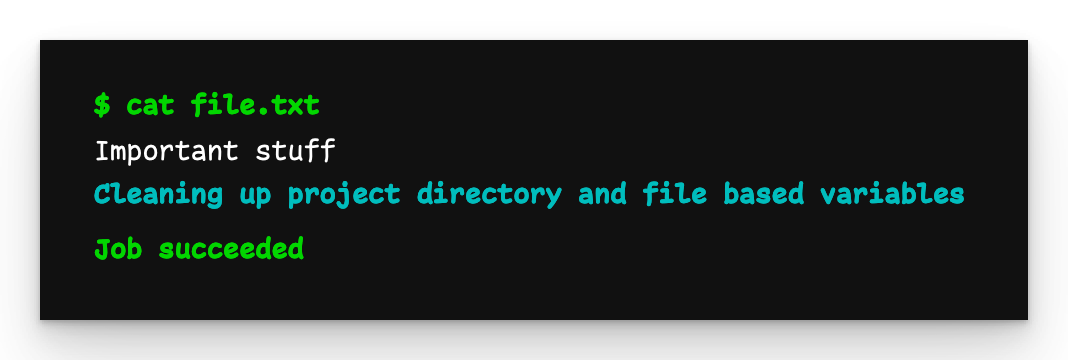

Child pipeline output

Here we see that file.txt was successfully passed to the child pipeline.

Including multiple child pipeline files

Up to now we’ve only used one child pipeline file at a time, but it’s possible to include multiple.

You can find the source code in the reference repository.

We start with .gitlab-ci.yml:

parent-trigger-job:

trigger:

include:

- local: template.yml

- local: child-pipeline-a.yml

- local: child-pipeline-b.yml

When you do this, the two (or more) child pipeline files are merged into a single file and triggered as one pipeline. This allows you to define default elements, share templates and even create dependencies with needs.

The template.yml file consists of:

.my-template:

after_script: echo "I run at the end"

The child-pipeline-a.ymlfile is:

python-job:

extends: [.my-template]

script: echo "I am the Python job"

The child-pipeline-b.ymlfile is:

default:

before_script: echo "I am after_script"

docker-job:

needs: [python-job]

extends: [.my-template]

script: echo "I am the Docker job"

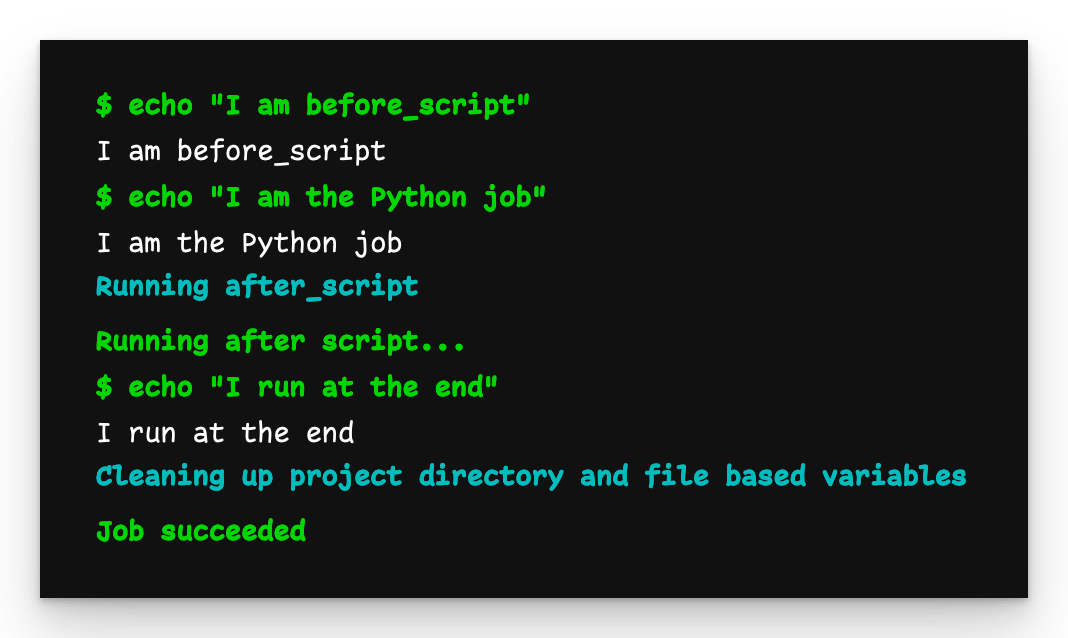

python-job

The python-job outputs what we expect. The default before_script defined in child-pipeline-b.yml was applied and the template was accessible.

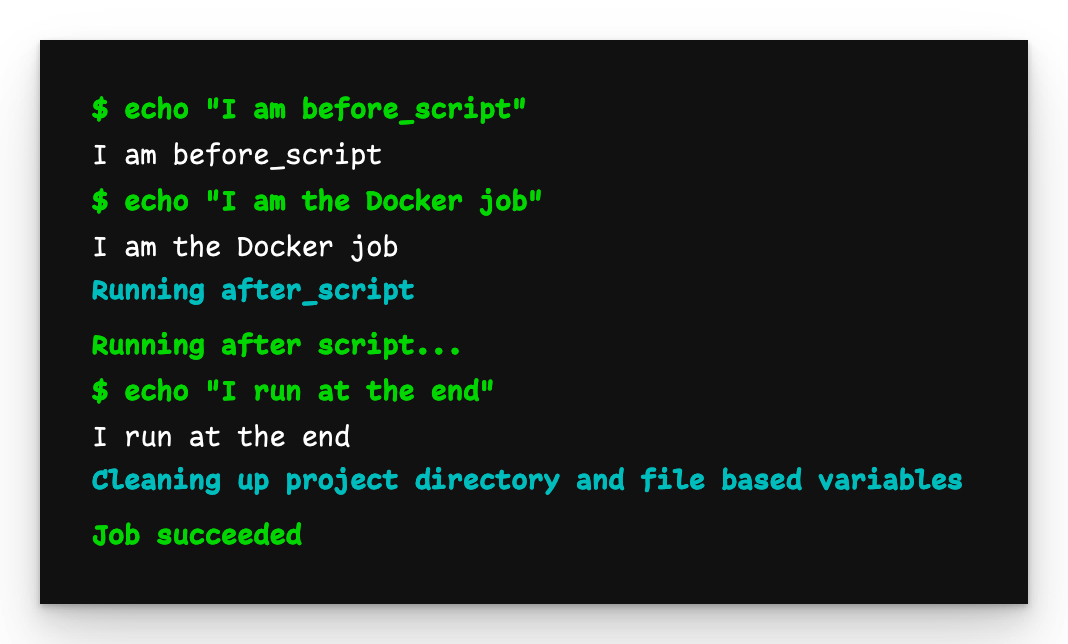

docker-job

The docker-job also outputs what we expect, plus it waits for python-job to finish before executing.

Including files from other repositories

All the child and grandchild pipeline code show this far has come from files in the same project, but it’s entirely possible to include files from other repositories.

You can find the source code in the reference repository and the other repository.

The code for the child-pipeline.yml file from the other repository remains the same:

child-job:

script: echo "I am the child job in the child pipeline"

The change comes in the parent repository’s .gitlab-ci.yml file:

parent-trigger-job:

trigger:

include:

- project: zaayman-samples/using-child-pipelines-in-gitlab-other

file: /child-pipeline.yml

ref: other-repositories

We’re no longer doing an include:local, but specifying a different project and ref (i.e. branch name or commit hash) and the child pipeline YAML file.

The output is what we expect it to be.

Note that no pipelines execute in the remote repository. The child pipeline file was fetched from the remote repository and run in the parent repository.

Safety concerns

Be careful when referencing pipeline code from repositories you don’t control. While it’s possible to inspect the remote code before using it, nothing prevents a bad actor from adding malicious code later. Since this code runs in the context of your repository, it will have access tho GUI-define variables and even secrets (which can be revealed with some base64 encoding). It’s better to fork the repository so you control the code completely.

Handling failure

By default, when a parent pipeline triggers a child, it doesn’t wait for the child’s completion status (success/failure) before determining its own status. While this has the benefit that a failed child pipeline doesn’t affect the status of the parent, that’s not always the behaviour you want.

Let’s start by showing the default behaviour. Let’s create .gitlab-ci.yml:

parent-trigger-job:

trigger:

include:

- local: child-pipeline.yml

The child-pipeline.yml file echoes a message and exits with a non-zero value, ensuring it fails.

child-job:

script:

- echo "Hello, I am the child job"

- exit 1

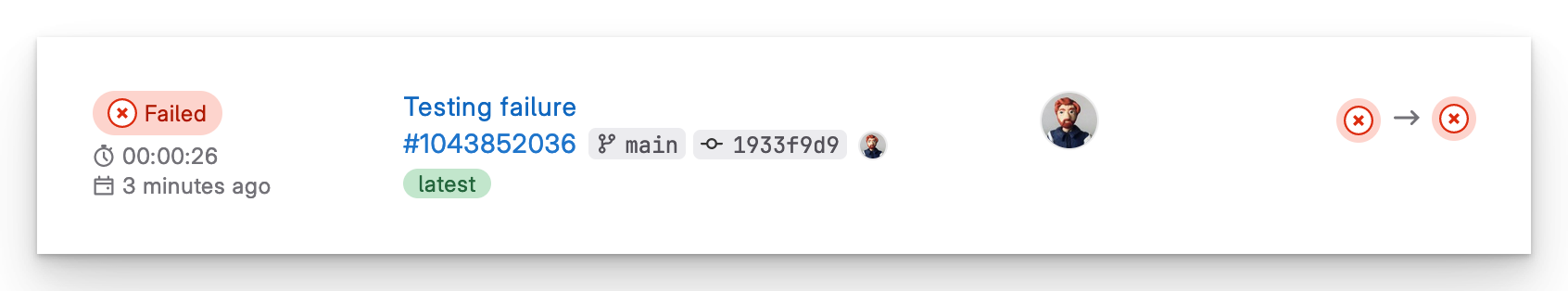

Parent pipeline succeeds even though the child pipeline failed

Notice that the parent pipeline passed despite the child pipeline failing. This is because, by default, the child pipeline runs independently of and in parallel with, the parent pipeline. If you want the child pipeline’s pass-fail status to affect the parent pipeline, update parent-job to use strategy:depend to ensure that the parent pipeline fails if the child pipeline fails.

parent-job:

trigger:

include:

- local: child-pipeline.yml

strategy: depend # Use this strategy

Parent pipeline fails because the child pipeline failed

Now the parent pipeline fails.

Using child pipelines to manage monorepos

In a previous blog, I suggested a way of managing a monorepo. However, because of the way GitLab coalesces all files into one and how its rules work, essentially all subdirectories of the monorepo are ‘executed’, but only the desired one completes. This is fine for a small monorepo, but can become unwieldy if it has many sub-repositories.

You can find the source code in the reference repository.

By using child pipelines, you simplify the mechanism that triggers the activation of the necessary pipeline in the subdirectory.

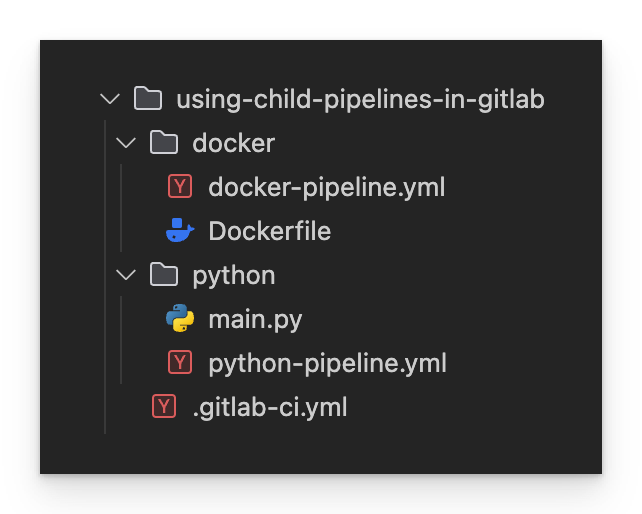

We start by creating a docker subdirectory that will be its own sub-repository within the monorepo. Inside that directory we place a Dockerfile and a docker-pipeline.yml file:

default:

image: docker:latest

docker-job:

script: echo "Docker job"

The contents of the

Dockerfiledoesn’t matter as wewon’t be doing anything with it for this example. It’s just there so there’s a file to change in the sub-repository that will trigger the pipeline.

We then create a python directory with a main.py file and a python-pipeline.yml file:

default:

image: python:latest

python-job:

script: echo "Python job"

Again, the contents of

main.pydoesn’t matter here.

Lastly, we create the .gitlab-ci.yml file:

docker-trigger-job:

rules:

- changes: [docker/**]

trigger:

include:

- local: /docker/docker-pipeline.yml

python-trigger-job:

rules:

- changes: [python/**]

trigger:

include:

- local: /python/python-pipeline.yml

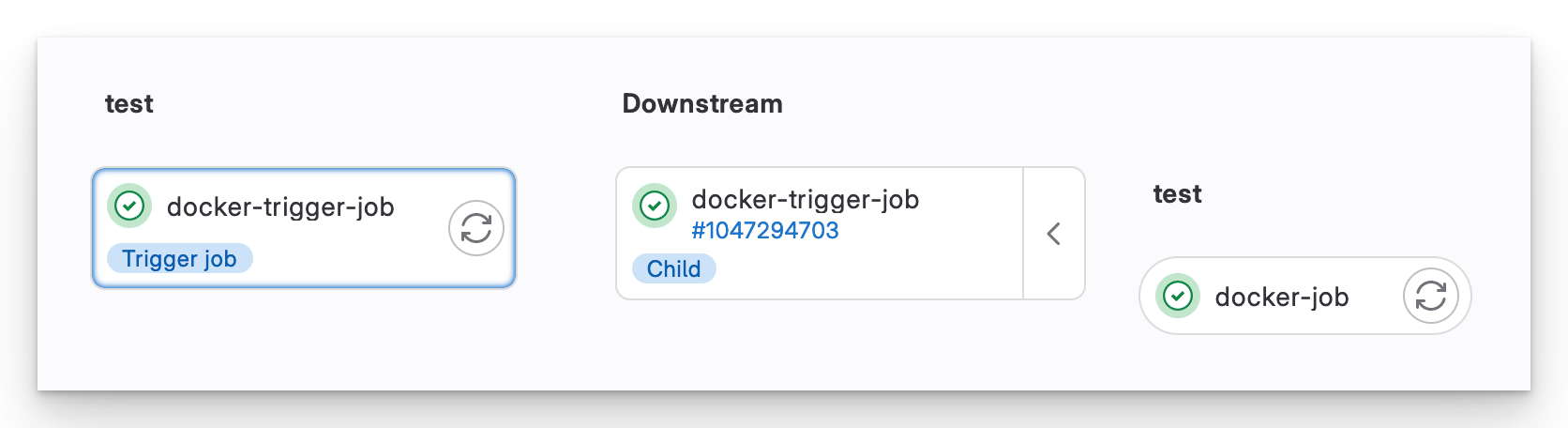

In the previous blog, all sub-repositories’ pipeline files were included regardless of in which directory a change was made. The specific rules governing which jobs ran had to be extended by each job. Now, the rules are expressed once, in one place, to determine which specific pipeline file to trigger. We are now also free to use a different default for each pipeline.

The final directory structure looks like this:

Final directory structure

If we push a change to docker/Dockerfile, only the Docker child pipeline is triggered.

A monorepo Docker child pipeline

Child pipelines is a much cleaner way to manage a monorepo, allowing each team to customise their individual pipeline without fear of affecting anyone else.

Conclusion

Like many modern technologies, GitLab pipelines have many ways of achieving the same solutions. Whether you’re joining a team that already uses child pipelines or you want to break up your existing pipeline code into smaller, more reusable units.