Not so long ago, I attended Graph Café, a nice type of meetup where there is no formal agenda, but there is just a series of lightning talks with beer inspired breaks in between. Graph Café’s are organized every so often by the Graph Database – Amsterdam meetup group. Naturally, my friend Rik van Bruggen, kindly and without any pressure had asked me to also do a lightning talk, so I had to come up with something. Neo4j 2.0 was released recently and the Graph Café was actually for celebrating this occasion. One of the new features in 2.0 is a major overhaul of the Cypher query language. I wanted to find out how much you could do with the query language in terms of creating functionality. My challenge: implement different forms of recommendations purely in Cypher. And I’m not talking about the basic co-occurrence counting type of recommendations, but something less trivial than that. My lightning talk ended up being about creating a naïve Bayes classifier in Cypher, which kind of worked. Obviously, I couldn’t just leave it at that, so now I implemented the classifier and collaborative filtering (based on item-item cosine similarity) purely in Cypher. This post shows how.

Your Meetup.com neighborhood in a graph

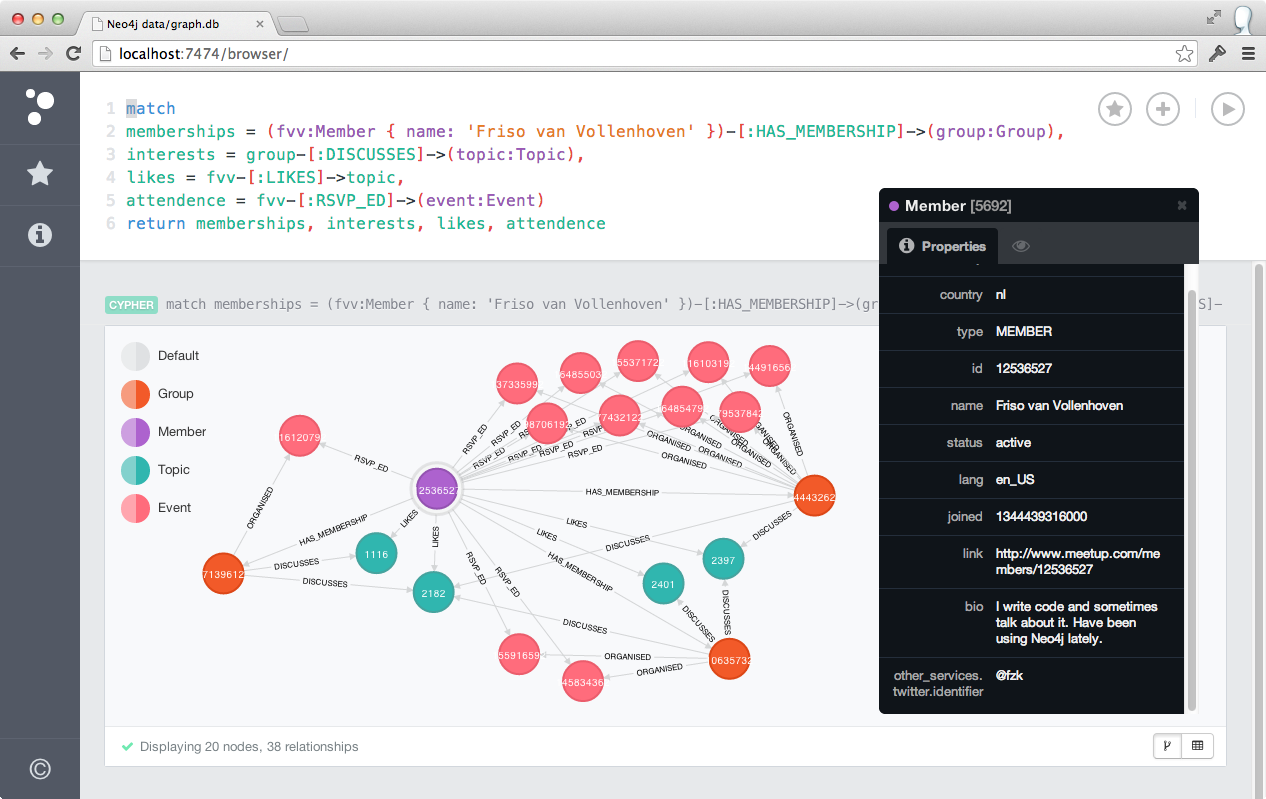

In order to do recommendations, we need a dataset with things in it that can be recommended. For this, I chose to grab data for a number of Meetup.com groups through their excellent API. This allows us to retrieve groups, their members, the members’ RSVP’s, the members’ interests and much more. Our graph contains several meetup groups with all members, topics that are of interest to members and to groups and all RSVP’s by members for each group. These are the possible relations and node labels (if this look awkward to you, go read about Cypher first):

(member:Member)-[:HAS_MEMBERSHIP]->(group:Group) (member:Member)-[:LIKES]->(topic:Topic) (member:Member)-[:RSVP_ED]->(event:Event) (group:Group)-[:ORGANISED]->(event:Event) (group:Group)-[:DISCUSSES]->(topic:Topic)

The graph is built using a simple Python script that makes the required API calls and populates the database using py2neo. Before we can do useful matching against the database, we need to create some indexes, so we can find things by name. Luckily, in the new Cypher, this is super easy!

create index on :Group(name) create index on :Member(name) create index on :Topic(name)

Now, let’s find me (Friso van Vollenhoven) and show all my group memberships, the topics I like, the topics my groups discuss and the events that I RSVP’ed for:

Are you a graph database person?

In our example, we are going to look for people that we can recommend the Graph Database – Amsterdam meetup group to. Basically, for each person in the database, we can ask: are you a graph database person? We will try to predict who would answer yes to that question. Those people will be the ones we can recommend the graph database group to.

So what makes a person a graph database person? One way to approach this, is to look at the topics that typical graph database people like versus the topics that other people like. We use the topics as a binary feature of a person and we will create a naïve Bayes classifier based on these features. For training we will assume that people already in the graph database group are graph database people and people who are in some other, non related group are non-graph database people.

In order to use the liking of topics as binary features for our classification, we need to determine the probabilities that a person likes a certain topic, both in general and for both classes that we’d like to classify (graph database person and non-graph database person). We can do this easily by just counting how many people like each topic. We do this for the entire training population and for the both classes. Also, we will separate the training data into two parts, so we can use one part as training data and one as test data to verify the accuracy of our classifier.

First, let’s see which groups we have in the data set.

match (group:Group) return group.name

Which gives us:

group.name

-----------------------------------------------------

The Amsterdam Applied Machine Learning Meetup Group

Netherlands Cassandra Users

AmsterdamJS

Graph Database - Amsterdam

Amsterdam Language Cafe

Open Web Meetup

Amsterdam Photo Club

'Dam Runners

Amsterdam Beer Meetup Group

The Amsterdam indoor rockclimbing

(10 rows)

Now, let’s mark two groups as training groups by adding a label.

match (graphdb:Group { name:'Graph Database - Amsterdam'}), (photo:Group { name:'Amsterdam Photo Club' }) set graphdb :Training, photo :Training

In the training groups, select half of the members as training data by adding a label to those nodes as well (hint: don’t run this query multiple times).

match (group:Group :Training):HAS_MEMBERSHIP]-(member:Member) where rand() >= 0.5 set member :Training return group.name, count(distinct member)

The query returns the number of members that were chosen as training data per group.

group.name | count(distinct member)

----------------------------+------------------------

Amsterdam Photo Club | 189

Graph Database - Amsterdam | 106

(2 rows)

The result shows us how many people went into the training data set for each group. We need to remember those number for later reference, as they will be the denominators in some of the calculations we’ll do.

Learning by counting

Let’s look at how liking different topics adds to the chance of someone being a graph database person. For this, we also need to know the total number of people in the training data. Of course we can add up the numbers above, but where’s the fun in that. Let’s query for it.

match (member:Member :Training)-[:HAS_MEMBERSHIP]->(grp:Group :Training) return count(distinct member) as total_members

We need to keep this number for later reference.

total_members

---------------

295

(1 row)

The nice thing about naïve Bayes is that for binary features, it’s mostly just counting and multiplying. The problem is that we need a way to remember these counts. Cypher is stateless and declarative, so we have no way to kind of keep things around in memory in between queries (AFAIK). To work around this, we are just going to store the count in the graph itself. First, we set the likes from all members on each topic. Notice how we add 1 to the actual like count. We will later see why this is.

match (topic:Topic):LIKES]-(member:Member :Training) with topic, count(distinct member) as likes set topic.like_count = likes + 1 return count(topic)

The query returns the number of updated topics.

count(topic)

-----------------------

1111

(1 row)

We do the same for likes from graph database members.

match (grp:Group :Training { name:'Graph Database - Amsterdam'} ):HAS_MEMBERSHIP]-(member:Member :Training)-[:LIKES]->(topic:Topic) with topic, count(distinct member) as likes set topic.graphdb_like_count = likes + 1 return count(topic)

Which updates 502 topics.

count(topic)

--------------

502

(1 row)

Finally, we need to do the same for the non-graph database people.

match (graphdb:Group :Training { name:'Graph Database - Amsterdam' }), (other:Group :Training):HAS_MEMBERSHIP]-(member:Member :Training)-[:LIKES]->(topic:Topic) where not graphdb:HAS_MEMBERSHIP]-member with topic, count(distinct member) as likes set topic.non_graphdb_like_count = likes + 1 return count(topic)

Which updates another 816.

count(topic)

--------------

816

(1 row)

Cool. Now we have all ingredients to see if we can classify a member as a graph database person. Let’s give it a try with my friend Rik. You can see in the query that we use coalesce to account for topics that we have not seen in our training data. We give these topics a default value of 1. However, this would not be fair to the topics that are actually present once. As a solution we could add 1 to those topics, but then it wouldn’t again be fair to the topics that were actually present twice, which is why we add 1 to all the topic counts. Which is the +1 that we saw in the earlier queries where we set the counts on the topics. This is a form of smoothing the data based on the assumption that really rare properties occur less than the ones in the training data.

Now, let’s look at how the different topics that Rik likes add to the fact the he may or may not be a graph database person. We take a look at all topics that Rik likes and return the probabilities of a graph database person liking these versus the probability of a non-graph database person liking these. We can use these to determine the conditional probabilities of someone being a graph database person based on the presence of a topic using Bayes’ theorem.

match (member:Member { name : 'Rik Van Bruggen' })-[:LIKES]->(topic:Topic) return topic.name, has(topic.like_count) as in_training, ( (coalesce(topic.graphdb_like_count, 1.0) / 106.0) * (106.0 / 295.0) ) / (coalesce(topic.like_count, 1.0) / 295.0) as P_graphdb, ( (coalesce(topic.non_graphdb_like_count, 1.0) / 189.0) * (189.0 / 295.0) ) / (coalesce(topic.like_count, 1.0) / 295.0) as P_non_graphdb

Liking Neo4j and Graph Databases really increases the likelihood of being a graph database person. What a surprise! Topics exclusively present in the graph databse training group, will have a 1.0 probability, which sometimes results in > 1.0 because of rounding errors. We also return a boolean flag that tells us whether the topic was present in the training data. You can see that topics not present in any of the classes in the training data, return a 1.0 probability on both sides, which is counterintuitive (and wrong), but for the classification it doesn’t matter.

topic.name | in_training | P_graphdb | P_non_graphdb

--------------------------------------+-------------+--------------------+----------------------

Data Science | True | 1.0 | 0.03225806451612903

Data Mining | True | 1.0 | 0.047619047619047616

Data Analytics | True | 0.9818181818181818 | 0.03636363636363636

Game Development | False | 1.0 | 1.0

Video Game Design | False | 1.0 | 1.0

Mobile and Handheld game development | False | 1.0 | 1.0

Mobile Game Development | False | 1.0 | 1.0

Video Game Development | False | 1.0 | 1.0

Indie Games | False | 1.0 | 1.0

Independent Game Development | False | 1.0 | 1.0

Game Design | False | 1.0 | 1.0

Game Programming | False | 1.0 | 1.0

Data Visualization | True | 1.0 | 0.047619047619047616

Software Developers | True | 0.9090909090909091 | 0.10909090909090909

Open Source | True | 0.8823529411764706 | 0.1323529411764706

Java | True | 0.9600000000000002 | 0.08

Java Programming | False | 1.0 | 1.0

mongoDB | True | 0.9615384615384616 | 0.07692307692307693

Big Data | True | 1.0 | 0.013333333333333334

NoSQL | True | 0.9836065573770492 | 0.03278688524590164

Graph Databases | True | 1.0 | 0.019230769230769232

Neo4j | True | 1.0000000000000002 | 0.020833333333333336

(22 rows)

Independence for all features!

Now let’s use those probabilities and combine them into a classification under the naïve assumption that liking topics is completely independent.

match (member:Member { name : 'Rik Van Bruggen' })-[:LIKES]->(topic:Topic) with member, collect(coalesce(topic.graphdb_like_count, 1.0)) as graphdb_likes, collect(coalesce(topic.non_graphdb_like_count, 1.0)) as non_graphdb_likes with member, (106.0 / 295.0) * reduce(prod = 1.0, cnt in graphdb_likes | prod * (cnt / 106.0)) as P_graphdb, (189.0 / 295.0) * reduce(prod = 1.0, cnt in non_graphdb_likes | prod * (cnt / 189.0)) as P_non_graphdb return member.name, P_graphdb > P_non_graphdb

Once more, what a surprise. Rik is likely to be a graph database person! Note that we are not using the denominator as above. We can do this, because it’s the same for both classes and we only care about which of the two results is larger.

member.name | P_graphdb > P_non_graphdb

-----------------+---------------------------

Rik Van Bruggen | True

(1 row)

Now for the big question! In the entire dataset, how many graph database people are there, which are not already a member of the graph database group?

match (member:Member)-[:LIKES]->(topic:Topic), (graphdb:Group { name:'Graph Database - Amsterdam'}) where not member-[:HAS_MEMBERSHIP]->graphdb with member, collect(coalesce(topic.graphdb_like_count, 1.0)) as graphdb_likes, collect(coalesce(topic.non_graphdb_like_count, 1.0)) as non_graphdb_likes with member, (106.0 / 295.0) * reduce(prod = 1.0, cnt in graphdb_likes | prod * (cnt / 106.0)) as P_graphdb, (189.0 / 295.0) * reduce(prod = 1.0, cnt in non_graphdb_likes | prod * (cnt / 189.0)) as P_non_graphdb with P_graphdb > P_non_graphdb as graphdb_person return graphdb_person, count(*)

Well, it turns out that our classifier believes there are 863 people potentially addicted to graph databases, without having joined the group already.

graphdb_person | count(*)

----------------+----------

False | 1724

True | 863

(2 rows)

The next obvious question now is: how accurate are those results? Because we kept half of the data in our labeled data set apart as a test set, we can now use that to figure out how accurate our classifier is by creating a confusion matrix (although it doesn’t look like a matrix in our output, but you get the point). Let’s have a look.

match (group:Group :Training):HAS_MEMBERSHIP]-(member:Member)-[:LIKES]->(topic:Topic) where not (member:Training) with group, member, collect(coalesce(topic.graphdb_like_count, 1.0)) as graphdb_likes, collect(coalesce(topic.non_graphdb_like_count, 1.0)) as non_graphdb_likes with group, member, (106.0 / 295.0) * reduce(prod = 1.0, cnt in graphdb_likes | prod * (cnt / 106.0)) as P_graphdb, (189.0 / 295.0) * reduce(prod = 1.0, cnt in non_graphdb_likes | prod * (cnt / 189.0)) as P_non_graphdb with group, P_graphdb > P_non_graphdb as graphdb_person return group.name, graphdb_person, count(*)

The results:

group.name | graphdb_person | count(*)

----------------------------+----------------+----------

Graph Database - Amsterdam | False | 3

Graph Database - Amsterdam | True | 117

Amsterdam Photo Club | False | 157

Amsterdam Photo Club | True | 10

(4 rows)

As it turns out, we have 10 false positives, so we wrongly classify about 7% of non-graph database people as graph database people. If we wish to improve on this, there are several options. One is to investigate the details of the false positives by doing manual exploratory analysis and as a result of that come up with potentially better features. The other, obvious one is: MORE DATA! Go for the latter if you can; it’s cheaper than spending numerous hours improving your model.

Production ready?

The above solution works. However, there is one thing: we need to store the like counts for topics in the graph itself for things to work. The good thing is that this actually creates a denormalized (does that exist in a graph database?), pre-aggregated view of some required data for the classification. This makes the classification process faster. On the downside, setting and updating the counts is a graph global operation which also writes back to the graph.

If we were to do this classification just once and then forget about it, it would be nicer to keep the counts in memory and not in the graph. We could open a feature request for a Cypher based scripting language that allows to set variables during script execution which are reusable throughout the script.

On the other hand, if you need to run the classifier all the time, it would be nicer to have the counts stored in the graph, but keep them updated when things change. Another feature request: triggers.

Targeting entire groups

Classifying each person individually is a lot of work. It can be problematic scaling such an approach. Can’t we just target entire meetup groups that somehow resemble our graph database meetup group? Of course we can. We can use collaborative filtering to figure out which groups are most similar to ours.

The absolute simplest (stupidest) thing you can do is just assume that groups that have the most members in common with our group are most similar and hence will also like graph databases (as a group). The issue with this is that it tends to favor larger groups over smaller ones (because they will have more members in common). Because of that, we will normalize the count of members in common to the target groups size.

match (us:Group { name: 'Graph Database - Amsterdam'}):HAS_MEMBERSHIP]-(member:Member)-[:HAS_MEMBERSHIP]-(other:Group) with other, count(distinct member) as coo match other:HAS_MEMBERSHIP]-(person:Member) return other.name as name, coo, (coo * 1.0) / count(distinct person) as rank order by rank desc

This result implies that we should target the member of the Netherlands Cassandra Users meetup group when we are looking for new members for the graph database group. This seems nice, but there are still issues. First of all, we see that the Open Web Meetup scores relatively high (ranked 3rd), but it is a very small group, so it needs only a few members in common to reach a large fraction in common, so the result may not be very significant. We could try to take the number of members in the target group into account to create a confidence interval of which we could use the lower bound as the actual score (here’s a nice explanation of the concept), but we’ll save that maybe for later.

name | coo | rank

-----------------------------------------------------+-----+-----------------------

Netherlands Cassandra Users | 31 | 0.2246376811594203

The Amsterdam Applied Machine Learning Meetup Group | 55 | 0.2029520295202952

Open Web Meetup | 4 | 0.10256410256410256

AmsterdamJS | 36 | 0.06557377049180328

'Dam Runners | 5 | 0.009433962264150943

Amsterdam Beer Meetup Group | 4 | 0.005934718100890208

Amsterdam Photo Club | 2 | 0.005154639175257732

Amsterdam Language Cafe | 2 | 0.0027397260273972603

(8 rows)

Another issue with this result is that is only looks at group membership as input. It is debatable whether group membership is a really strong indication of interest of a member. Anyone can be a member of many meetup groups as joining is easy and free. Perhaps a lot of people join a group just to check it out once and then never interact with the group anymore, but are still listed as a member. In order to work around this, we are going to use the RSVP’s of people to see how often they actually, physically interact with the group. More RSVP’s means more interest in the group. Once more, we need to of course normalize for the number of meetups a group actually organizes. We are going to use the number of meetups attended as a fraction of the meetups organised by a group as a score for the interest that each member has in a group. We can use these score to calculate a similarity of two groups based on the similarity in the way members interact with the group. One way of doing this is collaborative filtering using cosine similarity as a similarity measure (as opposed to pure co-occurrence in the example above). So, here it is:

match (us:Group { name:'Graph Database - Amsterdam'})-[:ORGANISED]->(graph_meetup:Event) :RSVP_ED]-(member:Member)-[:RSVP_ED]->(other_meetup:Event) :ORGANISED]-(other:Group) where us other with us, other, member, count(distinct graph_meetup) as graph_rsvp, count(distinct other_meetup) as other_rsvp match us-[:ORGANISED]->(graph_meetup:Event), other-[:ORGANISED]->(other_meetup:Event) with us, other, member, (graph_rsvp * 1.0) / count(distinct graph_meetup) as graph_score, (other_rsvp * 1.0) / count(distinct other_meetup) as other_score with us, other, collect(graph_score * other_score) as score_product, collect(graph_score * graph_score) as graph_score_squared, collect(other_score * other_score) as other_score_squared, count(distinct member) as coo where coo > 1 return us.name, other.name, coo, reduce( sum = 0, prd in score_product | sum + prd) / ( sqrt( reduce(sum = 0, x in graph_score_squared | sum + x) ) * sqrt( reduce(sum = 0, y in other_score_squared | sum + y) ) ) as cosine_similarity order by cosine_similarity desc

And in the results you can see that: a) when you don’t just look at membership, but at meetup attendance, there are only three other groups that have actual co-occurrence with the graph database group and b) The Amsterdam Applied Machine Learning Meetup Group now scores better than the Cassandra group.

us.name | other.name | coo | cosine_similarity

----------------------------+-----------------------------------------------------+-----+--------------------

Graph Database - Amsterdam | The Amsterdam Applied Machine Learning Meetup Group | 38 | 0.7815846503441577

Graph Database - Amsterdam | Netherlands Cassandra Users | 18 | 0.6727954587015834

Graph Database - Amsterdam | AmsterdamJS | 18 | 0.4432132175425046

(3 rows)

Conclusion

Yes, you can create a complete recommender just in Cypher. It would be nice to have triggers and some scripting environment, though.