Distance affects performance, going further away latency can

easily reach a third or half of a second for a round-trip. This

could be a bummer when you serve customers globally. Luckily

there’s..

Global Accelerator

Global Accelerator solves a few common DNS problems1

as it’s not relying on IP address caches. It has 2 static IPv4

addresses as a single fixed entry-point for users to connect through and

there’s no DNS configuration for you to maintain.

The 2 static IPv4 addreses are hosted in independent network zones

for fault tolerance. Similar to an AZ, a network zone is an

isolated unit with its own set of physical infrastructure. When

you configure an accelerator, if one IPv4 address from a network

zone becomes unavailable due to IP address blocking by certain

client networks, or network disruptions, then client applications

can retry on the healthy static IP address from the other isolated

network zone.

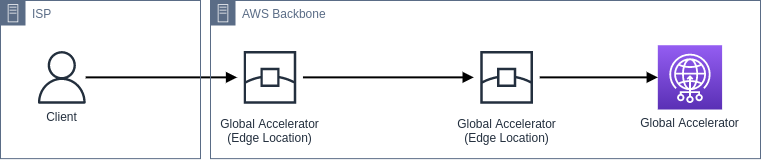

As the IPv4 addresses are announced from AWS its globally

distributed edge locations, your traffic can enter the

AWS Backbone network

as it’s faster to route traffic via edge locations then traversing

large parts of the internet.

Global Accelerator uses BGP (Border Gateway Protocol) Anycast to

route traffic over multiple paths (edge locations) to its

destination. I could explain you how BGP works in layman’s terms,

but I rather use Luc van Donkersgoed his wording, as I like the

way he explains it.

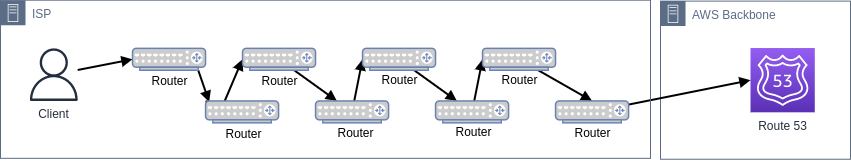

A BGP announcement is – ignoring its many technical intricacies –

a way for routers to announce to other routers ‘I am able and

willing to receive traffic for these IP addresses’. When another

router, for example at your internet provider, receives traffic

for one of these addresses, it will forward it to the router that

announced it and process that traffic. Every time a packet moves

from one router to another system, it’s called a hop. Every hop

costs processing time, so fewer hops means lower latency..

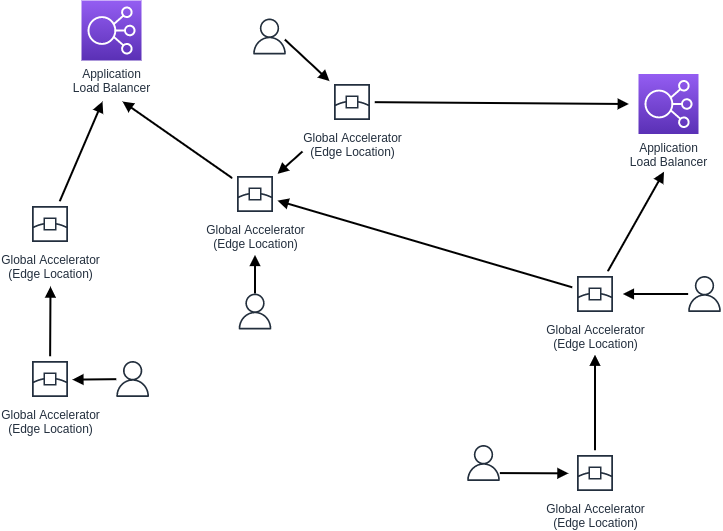

Perhaps there’s a way we can visualize this, it might just all

sound really abstract, right? Just remember that Global

Accelerator routes your traffic over the most optimal edge

location path towards its destination.

It’s important to note that the AWS Backbone network is very

efficient and has dedicated fiber lines that allows for fewer hops

between countries and continents. You’ll use your local ISP to

connect to the edge location instead of using your local ISP to

route all the way to a certain address which might take a very

long time including many network hops that can each introduce a

risk.

Route 53 latency-based routing

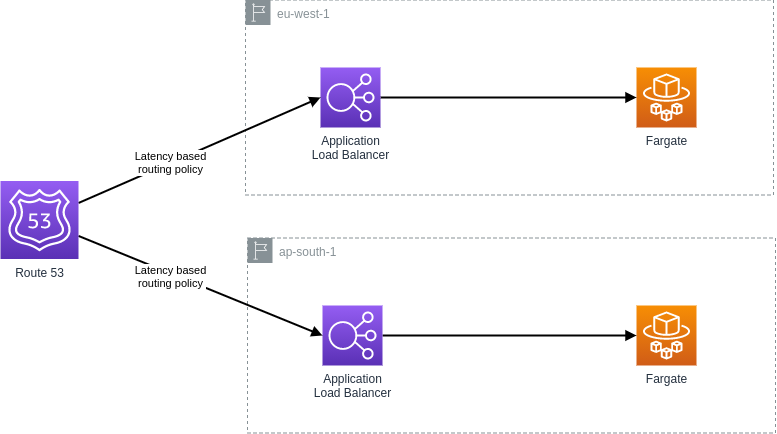

With latency-based routing, Amazon Route 53 can direct your users

to the lowest-latency AWS endpoint available. You might run an

active-active architecture where your stack spans multiple regions

(this can be done for disaster recovery and/or latency

advantageous). The Route 53 DNS servers decide2,

based on network conditions of the past X weeks, which

instances in which regions should serve particular users. I

currently live in Amsterdam, if company X decided to implement

latency-based routing and had their stack running in both Ireland

and Mumbai, I would likely be directed to eu-west-1 and a user in

Japan would likely be directed to ap-south-1.

So, how does this really differ from geolocation based routing policies?

It appears that both policies will route me (in Amsterdam) to

eu-west-1. However, they are not made to

just route me to the nearest resource. If company X now

decided to add the following requirement:

Due to compliance reasons, the Ireland customers data should be stored in Ireland and Mumbai customer data should be stored in Mumbai.

Now there’s more than just a subtle difference in these routing

policies, we now need to ensure something. Which we can’t do

with latency-based routing, there might’ve been multiple router

hick ups on our network path resulting in some requests being

offloaded to ap-south-1 (that would violate our agreement). Now

we could solve this additional requirement by using Geolocation

based routing, it allows Route 53 to route the traffic to the

resources according to the geographic location of the source

query.

Latency-based routing is based on latency measurements performed over a period of time,

and the measurements reflect these changes.

A request that is routed to ap-south-1 region this week might be routed to the eu-west-1 region next week.

When to use which?

Good question, no clue, lets figure out. We already know that Route 53 latency-based routing makes use of DNS telemetry and network latency to return the best latency record for a given query. Therefor it spends more time on the ISP network and the Internet than the Global Accelerator does.

Perhaps this little mnemonic will help you keep this in mind.

Latency-based routing enters the Backbone closest to the target backend.

Global Accelerator enters the Backbone closest to the client.

So the Global Accelerator spends more time on the AWS Backbone network. We can therefor conclude that if you’re running a multi-region architecture, you have to consider the distance between clients and resources and the number of regions your stack runs in. If it’s just a few regions, Global Accelerator performs better when it comes to routing traffic as the packets spend time on a better network (Backbone).

BGP Anycast can be slow to respond to network events such as link failures. Networks have to propagate BGP updates when conditions change. Luckily as earlier explained, Global Accelerator providers us with 2 static IPv4 addresses, and these will be served by diverse paths. The nice thing about having static IPv4 addresses is that clients can hardcode the static IPs in their DNS and firewall configurations, and use ordinary client retry behavior to drive the fault-tolerance.

We now know that latency-based routing uses constantly-running network latency measurements to figure out the best AWS region to send your traffic to. If your stack runs in many different regions, Route 53 sounds like the preferred option (as we would have just a few hops before reaching Route due to the small distance between clients and resources). Compared to the BGP event propagation Route 53 uses DNS health checks to respond to network events. These health checks are often faster than BGP Anycast.

Be aware that Global Accelerator performs TLS termination at edge. This is very useful as now the 3-way handshake happens at the edge location instead of the DNS server. Also, a little tip, increase the DNS TTL when using Global Accelerator as it’s a static IPv4 address.

Footnotes

- 1) DNS isn’t perfect, long TTLs reduce traffic on the Internet and prevent domain name servers from overloading, while short TTLs often cause heavy loads on authoritative name servers but are useful for swift disaster recovery. Too many devices cache TTL in their own way regardless of the value set in the DNS record.

- 2) Latency record measurements are continuously ran and usually measured over the span of a few weeks.

- AWS tool to compare Global Accelerator to the public internet.

- A nice session to learn more about Global Accelerator is this Re:Invent 2020 NET311 session.