Chaos Engineering is a practice that has its roots at Netflix. It born from the challenges of moving their workloads from the data centre to the cloud; the transient nature of the cloud affected the way that they build and operate a system at scale. The initial project was called Chaos Monkey, and it has almost 10 years.

Since then the community grew, fueled by Netflix practitioners. Today there are commercial and open-source tools, and we can see more initiatives in different communities. The technical practices had matured, and the knowledge started to spread in the IT world.

However, it is deemed perceived as a technical practice. Can we leverage Chaos Engineering as a management practice?

Role of a manager in today’s world

The role of a manager has changed. From a prescriptive approach, where the manager is leading the activities of people (managing and sometimes micromanaging), towards a supportive and transformational role. Today a manager needs to give structure and create a safe space for people and teams to excel in their fields. And the reason is that organisations are striving to be adaptative (anti-fragile), and it requires a new type of leadership.

Organisations require managers that take a leadership role in creating safety for both individuals and teams. Research shows that elite organisations have 5 capabilities with regards to culture and work environment: climate for learning, Westrum organisation culture, culture of psychological safety, job satisfaction and identity.

The reality is that sociotechnical systems are getting more complex, and it is not possible to have the system’s model in our heads. Today there are more components in the system, and to generate value, we have more inter-dependencies than we can imagine. As such, managers need to shift their mental models and practices. As an example, from a command and control style to a mission command style. Moving between these two styles requires a safe environment, where trust is the cornerstone.

But what are other practices a manager should embrace?

A bit of theory… And then we move on.

Options and costs of events, and their stabilisation

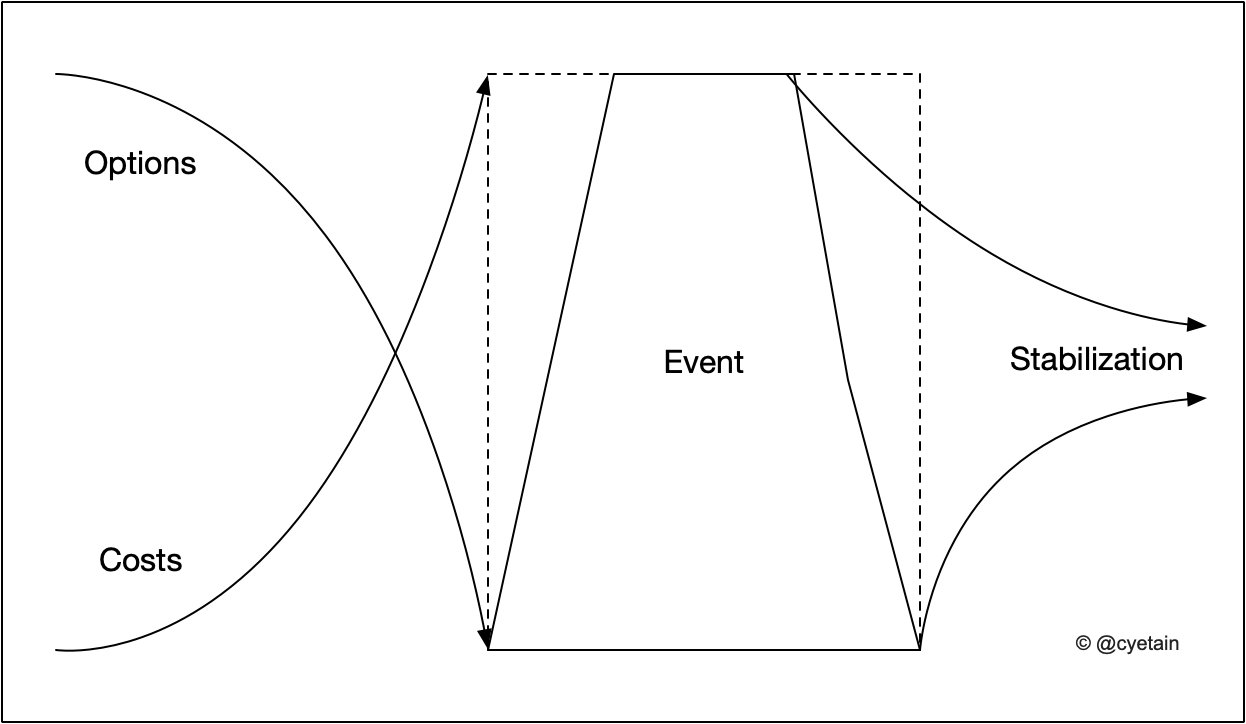

Jabe Bloom distilled a model for events. By event, it means anything that might affect the sociotechnical system. You can think about a spike in usage of your service because it hits the social media, holiday season, acquire and merge of companies, or the current pandemic. And everything in between. Some of the events are known upfront, others can be labelled as “unexpected”.

In a nutshell, in the pre-event phase, there are several options and their associated costs. As time goes by, and the event will happen, the options decrease, and the costs increase, until the point where the event starts. Note that you might be aware of the event or not. It depends on the ability to interpret the signals (weak or strong) and map those to create awareness. In the post-event phase, it tends to stabilise, both in terms of options and costs. You might hear the saying, “never waste a good crisis”. Organisations learn (I hope so), and can use different strategies to handle future events of the same type.

I’m providing a simple explanation of the model, and I don’t intend to go into complexity theory. It is a topic (several books maybe) on itself. My point here is that events can be costly if managers are not able to interpret the signals and create sound options. Back to the pandemic example, there are cases that organisations did the transition to working from home more manageable than others. I challenge you to map some hypothesis why. Also, the ones that are struggling with the change are incurring in higher costs, and it can be related to loss of productivity, market share, amongst others.

Now, let’s go to the next piece of theory…

Dynamic Safety Model

The Dynamic Safety Model was described by Jens Rasmussen in his paper titled Risk management in a dynamic society: a modelling problem. It can be illustrated by the following picture:

Casey Rosenthal and Nora Jones in the book Chaos Engineering, System Resiliency in Practice summarises the Dynamic Safety Model in Economics, Workload and Safety, where software engineers are good into understanding the limits and trade-offs with economics and workload. Still, we often miss the limits and trade-offs in safety. I agree with the analysis, and I learned in my career the same. Sometimes I underestimate my decisions towards safety, and other times I overestimate. Which made me retrospect based on the learnings of the past decade.

My retrospective

During my career, I performed different roles. As a software engineer, I often focus on solving the problem at hand, and as a manager trying to optimise the system environment for maximising the value delivering. And as interim CTO and consultant, I help organisations to change their operating models to accommodate a fast-changing world. As part of my retrospective, I discover that we try to induced change into an organisation, even when we take into consideration human aspects, and when a stressful event happens in the new operating model, people (and teams) usually fall back to the old behaviour.

Let’s have a scoped and narrowed example for the article’s sake. As a trivial example, I observed and worked together with organisations that moved from a siloed environment to end-to-end responsible teams. Where the responsibilities of creating and operating software are in different teams and/or departments, to end-to-end responsibly teams (we can call them teams working according to DevOps principles), where they need to design, build, release and operate the software in production. However, in an outage scenario, the teams have problems to react and fix the issue, due to the fact they are not used to operate in the new context. Hero culture often arises, where individual contributors are the ones solving the problems. In the long run, it is not sufficient and can lead to a dysfunctional and toxic culture.

I hope that you can relate to this example. There is a bigger and broader array of examples, and the theme of people’s ability to change and management capabilities to nurture it is a big topic. My colleague Thomas Kruitbosch and I have frequent conversations about it, and he keeps challenging me on the matter. 🙂

In the previous example, stress is introduced into the system. And teams tend to overestimate their decisions in the short time (e.g., when the event is still present in their memory), and underestimate in the medium and long time (e.g. when the event is a foggy memory). It matches with Casey and Nora analysis on the safety boundaries. Also relates to what Ben Mosior and Jabe Bloom describe as skilful coping. I believe that managers can create safety, and coach and mentor people to improve their decision-making process regarding the safety limits. At the same time, having a positive effect on the organisation culture towards an open and trustworthy culture.

Chaos Engineering and management

Well, we get back to the title of this blog post. Chaos Engineering! Not only as technical practice for the resilience of the technical system but more critical to the ability of an organisation to be truly adaptative, e.g., anti-fragile. A sociotechnical system has people and technology interacting, and as a manager that is responsible for part of the system, you have a tool to induce controlled experiments into the system; allowing teams and individuals to practice their ability to cope with an event (skilful coping). Not only if the technical system (software, infrastructure and everything in between) has the right measures in place, but if the processes (whatever processes an organisation adopts) is adequate for the context at play. It is very similar to the way of working of first responders, namely firefighters: 80% of their time is practising, and 20% of the time is in action.

And maybe you are wondering: “So what?”. Getting back to the theory chapter of this blog post, the lifespan of a company is full of events. Some with a more significant impact than others:

Based on my experience, and using Jabe’s model, the costs of an event and the period after stabilisation have higher costs. Bureaucracy to “prevent” events of the same type, leading to loss of productivity; health issues, such as anxiety and burn-out; people are leaving the organisation due to an unstable environment. And so on… However, using Chaos Engineering as a regular practice, the cost of events tend to decrease:

The costs of an event tend to decrease, and the stabilisation period is shorter. Using Chaos Engineering to inject controlled events into the system will help the organisation to test their options. Validate the different models against the reality (most of the times’ code and people behaviour), and to help people to build skills that allow them to cope with events that are not induced by Chaos Engineering. Using the initial examples, the holiday season, allows the organisation to exercise what means a significant outage during peak traffic during the holiday season, and how people and teams will react to that. Given the context of the exercise, e.g., controlled environment, stress levels are lower, and individual resilience is built. Also, from the technical side insights can be generated (there is enough literature on that). Based on the insights, individuals and teams can increase the sensitivity for the safety boundaries of the system, and managers can nurture the environment for it.

Last but not least, using Chaos Engineering will inject more events into the sociotechnical system. And as we know, in nature, biological systems evolve based on the events that they are exposed to. The same happens with the organisations: as more exposure to events the organisation has, the more adaptive it tends to be because it is building knowledge and practices on the potential options.

We can adopt Chaos Engineering as a management practice to lead the organisation to an anti-fragile state, creating a safe environment for people and teams to excel. As some organisations demonstrate, when the environment is safe, people unleash their superpowers.

Be aware that I’m not advocating for a silver bullet. There is more to it when it comes to creating a healthy organisation, where people feel safe and valued for their contribution. I will continue to explore this subject in the next blog posts.

How do you create a safe environment? What are the practices and tools that you use?

This article is originally published on my personal blog: Chaos engineering as management practice/