I have been a fan of GitHub Actions since the beta in the end of 2019. And the more I use them and create my own, the more I have this growing itch to see how these actions are made, how active the community is, and what we can do to improve this ecosystem. So I decided to do some research and see what I could find out. I already have a (now inactive) Twitter bot that scrapes the GitHub Actions Marketplace and stores that info for later use (unfortunately, the marketplace has no API to use for this).

Photo by Ashes Sitoula on Unsplash

I am also fascinated with the security aspects of using GitHub Actions for my workloads. My first conference session on this topic was at NDC London in January, 2021 and I have been advocating on these learnings ever since. That is why I also decided to run my usual security checks on the entire marketplace, starting with forking them so I can enable Dependabot on the forked repositories.

The Marketplace shows us almost 15 thousand actions that are available for us to use 😱. That means there is lots of community engagement for creating these actions for us, but also lots of potential for malicious actors to create actions that can be used to compromise our systems. Do be aware that in this post I’ll only be taking actions into account that have been published to the marketplace. Since any public repo with an action.yml in the root directory (and a bit more options) can be used inside of a workflow, there are many more actions that are available to us that are not part of this research.

Note: I’ve updated the analysis to disregard the DevDependencies after that information was added to the API. This means that the numbers are lower than the ones in the original post: a large portion of the alerts where coming from DevDependencies.

Analysis of the actions from the GitHub Actions Marketplace

I created a new repo to run these checks using GitHub Actions by scheduling a workflow that runs every hour and checks the dataset for new actions that have not been forked to my validation organization yet. If you have more checks or type of information you would like to see, definitely let me know and I’ll add them to the workflow.

Some caveats up front:

- I could only load the information for 10.5 thousand actions. All the others have issues that makes it that I cannot find them anywhere. These are not included in the dataset for this analysis.

- Some have been archived by their maintainer, but still show up in the Marketplace. These are of course older and have more security issues in them. The actions are included in this analysis. I’m planning to remove these when the Marketplace doesn’t show them anymore.

- There are some actions where I could not parse the definition file (if used), often because of duplicate keys in their definition file. I’ve reached out to some of the maintainers to get those fixed, but also want to improve my method of loading these kinds of files. Currently the library I use for this does not support duplicate keys and throws unrecoverable errors when it finds them.

I’ve reported this information back to GitHub and they are planning to improve the freshness of the data in the Marketplace. Still, this is a good two thirds of the actions that are available in the marketplace, so this is a representable dataset to look at. Examples of actions that show up in the marketplace but will 404 when you want to load the detail information for them:

Additionally all this analysis is done on the default branch for the repository. I have one action for example that uses a Dockerfile in the main branch, but I am working on converting it to Node in another branch. This number should be small enough to have no significant impact on the overall analysis.

Overall stats – Action type

My first interest was analyzing the overall makeup of the actions. For example, you can define the actions in multiple ways: By the ecosystem they use: Node based (Typescript or JavaScript), Docker based or it can be a composite action.

| Type of Action | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Node based | 4,7k | 45% |

| Docker based | 3.7k | 35% |

| Composite | 1.6k | 16% |

This tells us that there is a lot of use for Docker based actions! That means that a lot of these actions do something more complex than you can do in a Node based action. They made a choice to have a slower action, since the Docker image needs to be build or downloaded, and then needs to be booted up. Compare that with a Node base action, that immediately starts to run. But, you can use whatever language and ecosystem that fits your action the closest.

Action definition setup

Next up was analyzing the setup of the action itself. You can define it in multiple ways in the root of your repository:

action.yml– This is the default way to define an action. It is a YAML file that contains all the information about the action.action.yaml– This is an alternate way to define an action that was available at the beginning of GitHub Actions and is therefor still supported.Dockerfile– This is another way to define a Docker based action. If you don’t provide anaction.ymloraction.yamlfile, this one will be picked up. This Dockerfile is used by the runner and will be build on the execution environment when the action is used. An alternative way is to define the Dockerfile link in theaction.yml(or yaml) file. I’ve not made a specific overview that indicates how many Docker based actions where defined in theaction.ymlfile and how many have a separate Dockerfile.

| Definition of the Action | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| action.yml | 9.2k | 89% |

| action.yaml | 700 | 7% |

| Dockerfile | 144 | 1% |

| Unknown | 300 | 3% |

This tells us that almost 90% of the actions have been defined with the action.yml file, which is indeed the way that is show in most docs and demos.

Docker based actions

For the Docker based actions I was interested to see how many actions use a pre-build image from a container registry and how many do not. If they use a local Dockerfile, it will have a potentially big impact on the startup time of the action. Even worse, those are harder to support on GitHub Enterprise Server, since those environments are usually locked down from the internet, for valid security reasons. Supporting one of these actions means also supporting the ecosystems in use, starting with the base container image (run security scans on them folks!) and then anything it uses: apt-get, yum, yarn/npm, pip, etc. This will bring in some significant overhead for the support team. I’d rather recommend a maintainer to use a remote image, preferably the GitHub Container Registry, since that is directly associated with the repo and can then be downloaded without any (significant) rate limiting.

| Docker based action | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Remote image | 550 | 15% |

| Local Dockerfile | 3.1k | 85% |

From that we learn that on-boarding and validating these Docker based actions will likely be a lot of work and will have significant impact on your runner setup: each time it is used, the base image will be downloaded and then the action will be build on top of that. This is a lot of overhead for the runner and will slow down the execution of the workflow. It also costs unnecessary bandwidth on the runner as well as extra compute power, which has an impact on the environment. All this is rather unnecessary if the maintainer would use a remote image, where the runner host can cache that image locally. Be extra aware of this if you are hosting ephemeral runners, that get deleted after they have executed a workflow job.

One of the next steps here is to analyze the remotely hosted images on where these are hosted.

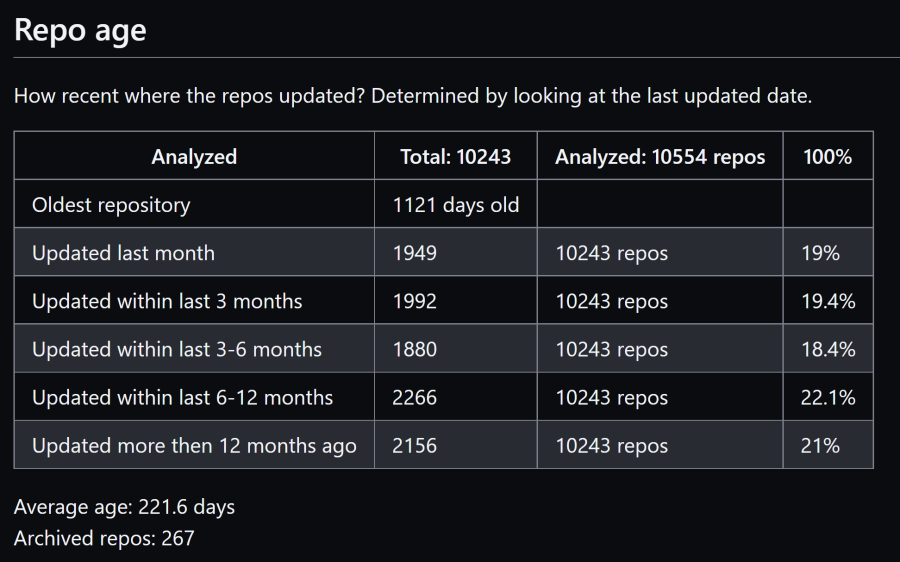

Repo age

The next thing I wanted to know was the repository age: what can we tell about the last time the repo had seen (any!) updates? If the action is not maintained at all, there is a good chance there might be something wrong with it (either in functionality, security or adding in new features).

I need to dive deeper to see if there are any patterns in the repo age:

- Do the 267!!! archived repos bring down the average age a lot?

- Do the most vulnerable repos match with the oldest repos?

- What about the last release that was made? All demos show that you need to include the version in the

usesstatements, so the last time the action has seen a release might be significant as well.

Security alerts for dependencies of the Actions

I’ve also forked over the action repos to my own organization and enabled Dependabot on them to get a sense of the vulnerable dependencies they have in use. Some caveats to this analysis are:

- Not every dependency will end up in the action itself, so a high alert from Dependabot will point to a ‘possibly’ vulnerable action. Since this is not something you can track automatically and see if this would be the case, we cannot be sure that the action itself is vulnerable.

- This only works for the Node based actions, which is 4.7k, so almost 50% of the analyzed actions. Dependabot does not support Docker at the moment.

- I’m only loading the vulnerable alerts back from Dependabot that have a severity of

HighorCritical.

I’m planning to add something like a Trivy container scan to the setup so that we get some insights from this as well.

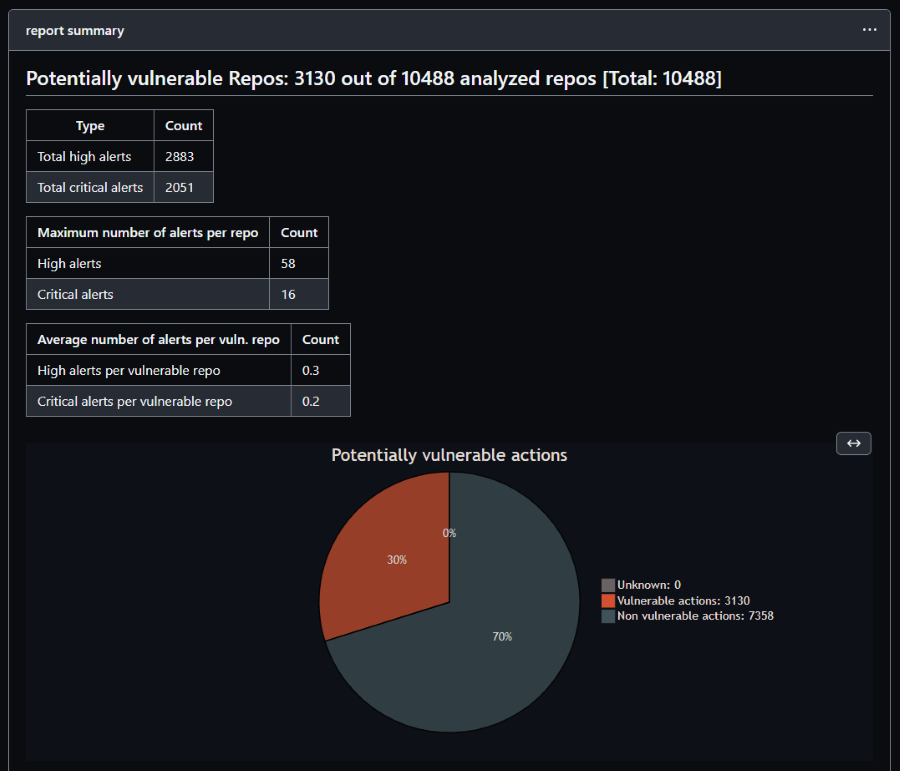

Security results

Of the 10488 scanned actions, 3130 of them have a high or critical alert 😱. And that is with only scanning the Node based and Composite actions, since the Docker based actions are not scanned yet. This is a way higher than I even expected and very scary! If your dependencies already are not up to date and thus have security issues in them, how can we expect your action to be secure? That calculates to 30s% of the actions that have one or more high or critical alert on their Dependencies.

To be complete: I have not filtered down the alerts to a specific ecosystem. Since GitHub Actions is one of the ecosystems Dependabot alerts on, there is a change these alerts come from a dependency on a vulnerable action for example, which would be unfair (since these will not end up in the action I am checking). Since there are only 3 actions in the GitHub Advisories Database, I expect this to be of zero significance, but still: good to mention.

Diving into the security results

I’ve also logged the repos with more 10 (high + critical) alerts to a separate report file and that file contains more than 600 actions!

The highest number of high alerts in one singe action, is 58. Since that repo happens to be Archived, it should not be in the actions marketplace at all, as well as the fact that this should not be used at all. Luckily it is only used by a small number of workflows. I’d rather see that the runner would at least add warnings to the logs for calling actions that are archived.

The highest number of critical alerts in one singe action, is 16. This repo is also only used by less then 10 other repos, so it is not a big impact. Since there is no API for finding the dependents that Dependabot finds, I cannot easily find out how many workflows are impacted by this.

I’ve checked some of the repos with a lot of alerts and found one example, that has 14 high severity alerts and 2 critical alerts. This action is used by 34 different public repos (so private could even be more!). One of these dependents is a repo with 425 stars and another has 6015 stars. That last one is producing a serverless CMS that will be delivered as 48 different packages into the NPM ecosystem. One of those packages sees more than a 1000 downloads a week! This is a lot of impact for a single action that could be prevented by enabling Dependabot. Of course, more analysis is needed for this case to see if the alerts are actually relevant for the action. This depends on what the action does and how it uses the dependencies.

Overview

In short, this is a top level overview of the security results:  So for all action repos I could scan, 30% have at least 1 vulnerability alert with a severity of high or critical.

So for all action repos I could scan, 30% have at least 1 vulnerability alert with a severity of high or critical.

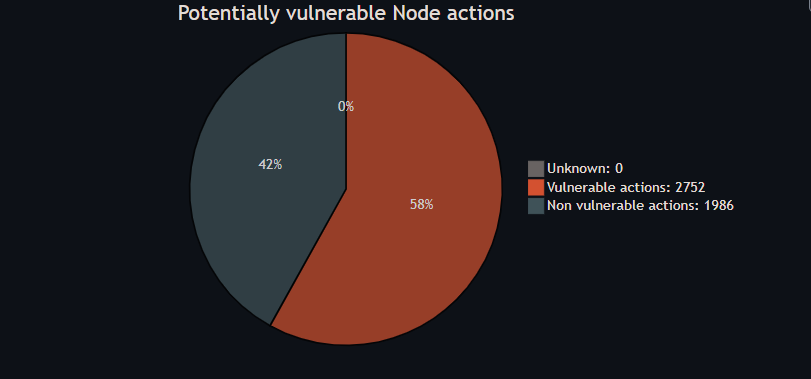

Node based actions

Filtering this down to only the Node action types, this becomes a lot scarier:  That is 58% of the Node actions that have at least 1 vulnerability alert with a severity of high or critical! And all demos and docs still indicate you can just use the actions as is and only hint at the security implications of that!

That is 58% of the Node actions that have at least 1 vulnerability alert with a severity of high or critical! And all demos and docs still indicate you can just use the actions as is and only hint at the security implications of that!

Want to learn how to improve your security stance fur using actions? Check out this guide I made: GitHub Actions Maturity Levels.

Conclusion

There is a lot of improvement for the actions ecosystem to be made. I would like to see GitHub take a more active role in this, by for example:

- Enforce certain best practices before you can publish an action to the marketplace

- Cleanup the marketplace when an action’s repo gets archived (work for this is underway)

- Add a security score to the marketplace, so that users can see how secure an action is, run at least these type of scans on the action repo and report it back to the end user

- Add a check that validates you also pushed a new release of the action to prevent maintainers to add Dependabot and keep their (vulnerable) dependencies up to date, but not actually release a new version of the action.

- Add API’s to not only the marketplace, but also Dependabot Of course, as maintainers of actions we are also in this together! It’s our responsibility to make sure our actions are secure and that we keep them up to date. I hope this post will help you understand why to do that!

Appendix

Maybe I can write a scanner action that looks at this information somehow. and inject that into the load used actions action that I created.

I’ll need to add this type of information for example to the Private Actions Marketplace setup for example.